|

Marc Chagall: Imagination, Memory, and Soul 1887-1985

|

|

|

|

Marc and Bella Chagall

|

|

|

The Lovers, 1928

|

|

"The quintessential Jewish artist of the twentieth century" was how Chagall was described by art critic Robert Hughes; and Picasso said of him, "When Matisse dies, Chagall will be the only painter left who understands what color really is."[1]

|

|

Marc Chagall in his studio in Paris

|

As a pioneer of modernism, he created a wide range of works, including paintings, book illustrations, stained glass, stage sets, ceramics, and tapestries, developing his unique style while living in St. Petersburg, Paris, and Berlin. He produced stained glass windows for the cathedrals of Reims and Metz, for the United Nations Building, and for the Jerusalem Windows in Israel, mosaic murals for the Metropolitan Opera in New York, and the painted ceiling of the Opéra Garnier in Paris.

|

|

|

The Fiddler, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

|

Born into a family steeped in Hasidic life, in Vitebsk, Russia, where half the population was Jewish, and where art was alien to his culture, he was unable to receive any art training.

|

|

|

The Milkmaid, 1929, Collection Federico Vogelius, Buenos Aires

|

Nevertheless, his mind pulsed with images from his childhood. At age 57, he wrote in a letter to the people of Vitebsk that he had painted no painting that "didn't breathe with your spirit and reflection."[2]

|

|

|

Over the Town, 1917-18, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

|

He came to Paris in 1922 because, according to him, that was where freedom in painting lived. It was a golden age for modernism, and Chagall was able to incorporate the new aesthetics into an absolutely individual style, remaining spiritually faithful to his native village of Vitebsk, Russia.

|

|

|

|

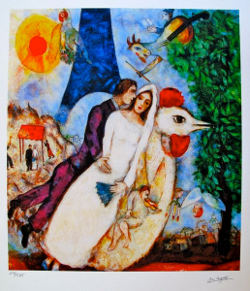

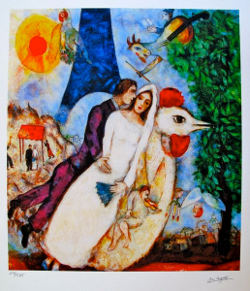

The Bride and Groom of the Eiffel Tower , 1938-39, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre George Pompidou, Paris

|

His historic achievement is that he opened up painting to the irrational world, to the imagery of the unconscious, of dreams, of memory. He made fantasy images as important as real images. That's his Russianness.

In Yiddish, one can speak several languages in the same sentence, and one can insert and mix words into the languages that contribute to it--Russian, Hebrew, German, Polish. Likewise, Marc appropriated features of several new languages of art--Cubism, Symbolism, Fauvism, Surrealism--and placed them side by side in the same painting.

|

|

|

Peasant Life, 1925, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY

|

His paintings are not just haphazard collections. The images operate in isolation, severed from their usual settings in historical, cultural, and personal domains, stemming from memory and imagination. However, the unity of their content is sanctioned not by logical or realistic coherence, but by their coexistence in Chagall's mind as soul and poetry.

Things naturally existing in a different space blend together. Time periods overlap. Separate events appear as simultaneous, as in a dream. His paintings are lit by the glow of memory.

|

|

|

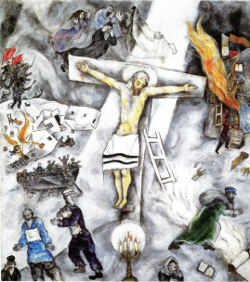

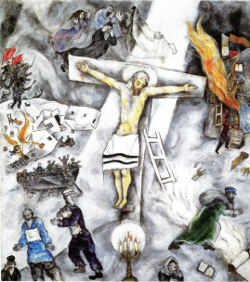

The White Crucifixion, 1938, Art Institute of Chicago

|

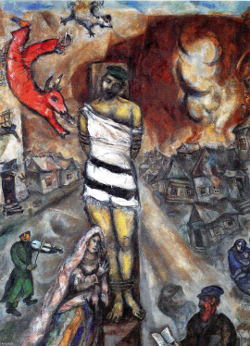

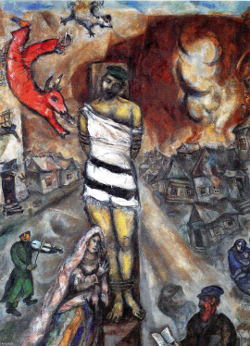

In spring of 1940, Marc and Bella Chagall moved from the Loire to Gordes, a hilltop village nine kilometers from Roussillon, thinking that they would be safer farther south. By October of that year, Marshall Pétain and his government in Vichy adopted anti-Jewish laws. Consequently, Chagall abandoned for a time his images of Vitebsk and of Bella and his dream world, and sought to express the oppression of Jews by picturing Jesus as a Jew tied to a cross in one painting, and a stake in another. The images came to represent his fear for the future of Jewry.

|

|

|

|

The Martyr, 1940

|

In the winter of 1940, Varian Fry of the American Aid Committee who ran a rescue operation by securing false documents to allow Jewish writers and artists to escape from Occupied France, passed along the invitation of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City to come to the United States. By April 1941, the Department for Jewish Affairs was established under Pétain's government in Vichy, and the Chagalls left Gordes for Marseille. On April 9, there was a police raid on the Hotel Moderne where he was staying. Chagall was arrested and taken in a police van. Bella went to Fry who warned the French police officer that Vichy would be gravely embarrassed and that he would be severely reprimanded for arresting one of the world's greatest painters. Half an hour later, he was released. A month later, on May 7, insisting on traveling with all of his paintings, 1.5 tons of them, the Chagalls crossed the Pyrenees into Spain. He returned to Europe in 1948, and naturally, effortlessly, became "the most important visual artist to have borne witness to the world of East European Jewry."[3]

|

I'm so grateful to have been led to include Marc Chagall in my novel. The more I learn about him, the more I adore him. I thank him for opening a new dimension of art, culture, and history for me, and for sanctioning a private dream world.

Sources:

[1]Jackie Wullschlager. Chagall: A Biography. Knopf, 2008..

[2] Benjamin Harshav, Marc Chagall on Art and Culture, Stanford University Press, 2003, p. 91.

[3]Michael Lewis, "Whatever Happened to Marc Chagall?" Commentary, October 2008, p. 36-37.

|

|