|

Complete reviews are below; just follow the respective periodical links.

Amazingly engrossing...lovely prose...[a] riveting, complex novel.

-- BOOKLIST

[Vreeland] creates a profoundly moving portrait of the creative process ... Highly recommended.

-- LIBRARY JOURNAL

Vreeland's love for Renoir is made palpable in this brilliant reconstruction.

-- KIRKUS REVIEWS

Vreeland achieves a detailed and surprising group portrait, individualized and immediate

-- PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

"She succeeds in making us see a painting - and the world - through a painter's eyes."

-- PHILADELPHIA INQUIRER

"Like the painters Vreeland writes about, she too is leaving her legacy - some of the world's finest examples of historical fiction."

-- SAN DIEGO UNION-TRIBUNE

"You don't just read this book: you can sniff, devour, fondle and listen to it."

-- CORVALLIS GAZETTE TIMES

"What stories indeed, delicately brushed to life in the pages of Vreeland's novel."

-- PARIS THROUGH EXPATRIOT EYES

"We Were Here, And We Loved"

-- ROCK AND SLING

BOOKLIST

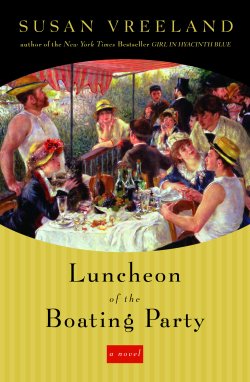

Once again--to the delight of her legion of fans--the best-selling author of Girl in Hyacinth Blue (1999) and The Passion of Artemisia (2002) imaginatively uses art history as the basis for a carefully constructed historical novel. Vreeland turns this time to French impressionist master Auguste Renoir's famous painting Luncheon of the Boating Party, which depicts a group of people (in 1880) enjoying leisure time on the terrace of a riverside restaurant. The current conditions in the life of the painter himself launch the author on an amazingly engrossing reinvigoration of the lives of the individuals who modeled for Renoir for that work, all of whom were actual people, and all are given a third dimension in Vreeland's lovely prose, beyon the two dimensions in which they were painted. Renoir's purpose was to create not only a masterpiece but also a work that would solve the dilemma of his continuing to "belong" to the impressionist school of which he has been a primary founder; in other words, he put his reputation on the line with Luncheon. There are, then, basically three levels of "atmosphere" swirling through the pages of this riveting, complex novel: Renoir's issues in composing the painting, the separate and interconnected lives of the 14 individuals appearing in it, and the spirit of la vie moderne, the new modes of living, thinking, and expressing as conducted by the French arts community at the time.

-- Brad Hooper, Booklist, American Library Association

Return to Review List

LIBRARY JOURNAL

One of the most significant paintings of the Impressionist period is Renoir's Luncheon of the Boating Party, and it's hard to imagine that a novel could do it justice. Yet this new work from Vreeland (Girl in Hyacinth Blue) does just that. She opens with an agitated Renoir eager to respond to criticism from Emile Zola, of all people, that the Impressionists have yet to produce a work of genius measuring up to their claims. Prodded by Alphonsine, whose family owns a restaurant on the river near his mother's home in Louveciennes, Renoir conceives a masterwork that will truly capture la vie moderne. He will depict a group of canotiers, or boaters, enjoying a festive lunch on the restaurant's veranda. Then he's off to collect models: Alphonsine, of course, and her brother; the painter Gustave Caillebotte; an actress and a model he has loved; and more. Vreeland weaves together their stories in unaffected prose that at first seems too modest for the painting it describes. In the end, she creates a profoundly moving portrait of the creative process and of a community of people who came together for a moment to help create one great work. Highly recommended.

-- Barbara Hoffert, Library Journal

Return to Review List

KIRKUS REVIEWS

In her fourth art-related historical, Vreeland (Girl in Hyacinth Blue, 1999, etc.) provides an in-depth look at one of Renoir's most famous paintings (its name is her novel's title).

Maison Fournaise, on the Seine outside of Paris, is one of Renoir's favorite haunts. One July day in 1880, the 39-year-old artist is at the restaurant/hotel/boat rental when he reads a Zola essay critical of the Impressionists. It goads him into action. He will paint a scene of boaters on the upper terrace, a wide canvas work that will surpass his Montmartre spectacle Bal au Moulin de la Galette. But time is short and money is tight. He has just two months to take advantage of the summer light. He must find money for paints, for modeling fees and for eight Sunday luncheons for his group. The female models must be women he could love. Alphonsine and Angèle are naturals; the former is the owner's daughter, the latter a bawdy child of Montmartre; both women glow with vitality. He adds the self-styled Circe, beautiful but temperamental, foisted on him by a salon hostess; she will provoke a crisis when she quits, refusing to be done in profile. Renoir finds a miraculous replacement in Aline, a 19-year-old seamstress he will marry, years later. There are other model problems: One man is involved in a duel; there is constant anxiety over the total number (13 must be avoided). Vreeland maintains the suspense while skillfully providing context. The traumas of the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune are only ten years distant; Alphonsine is a war widow, a male model is a wounded veteran. The politics of the art world are unremitting; the once-cohesive Impressionists are now split three ways. Degas mocks Renoir for seeing life through rose-colored glasses; too bad. Joyful conviviality is as valid as squalor. The finished product affirms Renoir's credo: "Art was love made visible."

Return to Review List

PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

Imagining the banks of the Seine in the thick of la vie moderne, Vreeland (Girl in Hyacinth Blue) tracks Auguste Renoir as he conceives, plans and paints the 1880 masterpiece that gives her vivid fourth novel its title. Renoir, then 39, pays the rent on his Montmartre garret by painting overbred society women in their fussy parlors, but, goaded by negative criticism from Emile Zola, he dreams of doing a breakout work. On July 20, the daughter of a resort innkeeper close to Paris suggests that Auguste paint from the restaurant's terrace. The party of 13 subjects Renoir puts together (with difficulty) eventually spends several Sundays drinking and flirting under the spell of the painter's brush. Renoir, who declares, "I only want to paint women I love," falls desperately for his newest models, while trying to win his last subject back from her rich fiancé. But Auguste and his friends only have two months to catch the light he wants and fend off charges that he and his fellow Impressionists see the world "through rose-colored glasses." Vreeland achieves a detailed and surprising group portrait, individualized and immediate.

Return to Review List

PHILADELPHIA INQUIRER

A perspective on art from the inside out

Vreeland's fiction explores a Renoir work.

It must be impossible to look at a painting for which we feel some special delight and not imagine how it was made. Was American Gothic meant to be taken seriously or satirically? What memories must the one-time Blue Boy have dredged up when, bankrupt, he sold the painting of himself by Gainsborough? And, of course, there's the eternal question of what Mona Lisa was smiling so enigmatically about.

Susan Vreeland has made a career out of such flights of fancy. Her best-selling novel, Girl in Hyacinth Blue, traced the fortunes of a fictional Vermeer painting from conception to the present day. The Passion of Artemisia was about post-Renaissance painter Artemisia Gentileschi, and The Forest Lover was about Canadian artist Emily Carr. Vreeland's last book, Life Studies, was a mostly clever story collection and preparation for her latest novel: Many of the pieces were looks at impressionists through the eyes of their acquaintances.

Luncheon of the Boating Party is Vreeland's most ambitious book yet, detailing the production of a single painting through seven points of view. Pierre-Auguste Renoir's most famous work was ripe for fictional treatment. Luncheon, housed at Washington's Phillips Collection, features 14 models, some famous, some not, with one not even conclusively identifiable. Renoir set out to make a masterpiece in 1880 and succeeded: "Figures, landscape, genre subject - all in one. Throw in a still life too," as he plans it in Vreeland's novel.

Impressionism aimed to capture the moment. Vreeland's novel aims to capture everything that went into making that moment. The painting may portray a group of friends lazily enjoying a summer afternoon on the Seine. But, as Vreeland details, it took weeks of execution, none of them easy. The starving artist sometimes had to choose between paying his models and purchasing paint, all while struggling to assemble his large party on successive Sundays before the summer light disappeared. An old lover forbidden to continue modeling by her possessive fiancé threatens to ruin the work entirely: Ever since The Last Supper, 13 figures in a painting have been bad luck.

"I make it a rule never to paint except out of pleasure," Renoir says. But the making of a masterpiece could be anything but.

The painting unfolds through the eyes of Renoir and six models. The painter aimed to capture la vie moderne, though his conception was different from that of contemporaries such as Zola, of whom Renoir scoffs, "He thinks he portrayed the people of Paris by saying that they smell." The new leisure of Parisians recovering from the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune was also part of modern life, Renoir insisted. He made no apologies for his sometimes sentimental work.

And his models represented all walks of Paris life. The man in the top hat was Charles Ephrussi, a rich art dealer who thought the scene was too vulgar for his wife to appear in, while the girl in the right foreground was a model and sometime prostitute who brought much joie de vivre to the proceedings. Vreeland explores their lives, to uneven effect. The quandary of Jeanne Samary, a famous actress and the former lover, offers a sharp look into the complicated life of women before liberation. But the few chapters from her perspective in the beginning of the book leave the reader wondering when she'll reappear. Neither do we really get to know Aline, the seamstress who saved the painting and eventually became Renoir's wife.

Most successful are the sections from the point of view of Alphonsine Fournaise, the daughter of the restaurateur whose terrace is pictured. (She's leaning on the railing.) Vreeland draws a moving portrait of a war widow whose involvement in art inspired the courage to make a life of her own. Renoir's a little bit in love with her, as he is with every woman he paints. The sensuality of Renoir's work is made clear in an astonishing passage near the end of the novel that, though it merely describes the artist making brush strokes, seems far too risque to reprint here. (It begins, "With the brush loaded and juicy - "")

Vreeland can be just as striking writing an entire paragraph on a raspberry. Though at times her writing feels a bit stilted, trying to capture the speech of a wide variety of people from a century ago, it can also reach transcendence. She has an uncanny ability to communicate the glories of art, whether she's putting real excitement into the first brush stroke or pointing out, quite naturally, tiny details in the painting that even frequent viewers of it might have missed.

Her delightful novel ends with such joy that it makes you forget its faults. Vreeland forces upon us, through sheer will, her belief in the life-transforming power of art. She succeeds in making us see a painting - and the world - through a painter's eyes. And couldn't we all stand to see the world more like a life-affirming Renoir?

-- Kelly Jane Torrance

Return to Review List

SAN DIEGO UNION-TRIBUNE

Sketches of la vie moderne

Susan Vreeland paints a luminous picture of Renoir and Paris

In her latest novel, Luncheon of the Boating Party, Susan Vreeland, like a god, breathes breath into the long dead Pierre-Auguste Renoir, French painter (1841-1919), and the man comes to life.

Not only does Renoir live and breathe, but the Paris of 1880 bustles with the corporate and private lives of her people. In this, her fourth novel, San Diego author Vreeland again demonstrates her mastery of historical fiction through which she has already won international acclaim. Her novels have been translated into 25 languages and have made the best-seller lists. One of the most startling details of Vreeland's rise to literary prominence is that writing is a second career for her, one she came to after 30 years as a teacher of high school English and ceramics.

Luncheon of the Boating Party, like her previous novels - Girl in Hyacinth Blue (2000), The Passion of Artemisia (2002) and The Forest Lover (2004) - explores the life and work of a renowned artist. The title of the current novel is taken from Renoir's painting - Le Déjeuner Des Canotiers - which depicts a Sunday afternoon gathering of friends on a café terrace along the Seine.

Structurally, the novel spins out from the painting. As Renoir contemplates undertaking the painting, he is forced to consider age-old artistic conflicts. Should he continue painting traditional portraits for wealthy patrons and receive a generous income for his labor, or should he cast his lot with the experimental artists engaged in a new style called impressionism? Casting his lot with the new artists and the new art form may break fertile ground, but may well lead to poverty:

"That was the more perplexing question, the underlying issue agitating him lately. Impressionist or traditional? It was all tied up with that other question - whether to withdraw completely from the Impressionist circle, continue to submit to the academic Salon and betray his friends, or to return to the Impressionist group he had helped form ... he loved his friends - Claude Monet, Gustave Caillebotte, Camille Pissarro, Alfred Sisley, Paul Cézanne, and Berthe Morisot. ... Who was he really betraying by turning out one society portrait after another? The group? Himself? Both?"

Within his own thinking, Renoir properly positioned his debate in these terms: "One road ... to poverty, the other to stagnation." To complicate matters, Emile Zola, influential literary and art critic, wrote of the impressionists: "All remain unequal to their self-appointed tasks. That is why, despite their struggle, they have not reached their goal; they remain inferior to what they undertake; they stammer without being able to find words."

Edgar Degas chides him: "Prettying up your sitters so their husbands will throw their money at you. Renoir, you have no character at all to continue churning them out."

But even Renoir had his doubts about the impressionists. What he wanted to do in his own art was to create a work bringing together a combination of styles. For the faces of his models, he wanted a more traditional and classical style, and for the background, the looser and more distinct strokes of the impressionists. The figures in his painting should be luminous - a flawless blending of color and form, each figure an individual work of art.

He also wanted a painting that showed Parisians enjoying happy times. The French had been defeated in the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) and the effects still lingered, but the French had begun rebuilding their lives and once again were taking pleasure in good food, good wine, amiable company and leisure time. In 1880, new contrivances were entering daily life, including the steam-powered bicycle, and a new century was just around the corner. Renoir felt this sense of entering a new era, la vie moderne. All of this, he wanted to capture in his painting - the good life among friends on a Sunday afternoon, their faces alive with promise, hope and the flirtations of youth.

Renoir makes his decision: He will stake his reputation on the painting he envisions. He turns down a lucrative offer to paint portraits for a wealthy patron and sets out to bring his artistic vision to fruition.

His first tasks, to recruit models and to acquire paints and canvas, take him into the streets and establishments of 19th-century Paris. For the reader, this offers a grand view of the city. Renoir needs 14 models for his large canvas. He wants to hand-select his figures, avoiding the model market where young woman gathered in hopes of being recruited - "laundresses, dressmakers' apprentices, and grisettes in gray muslin dresses living off students in the Latin quarter lined up around the circular fountain, hoping to be picked by painters looking them over."

His models include a fellow painter, a performer in the Offenbach opera, an Italian journalist, [and] two actresses, the son and daughter of the café owner where he stages his painting...Seven of the models serve as viewpoint characters, telling their personal stories and providing details of their daily lives. Multiple viewpoint characters serve as multiple eyes on the city and provide greater access to Paris in 1880.

The modeling sessions are all-day events including boat rides and a three-course luncheon with wines and liqueurs. Renoir wants his models to enjoy themselves. While they must hold their positions, they are encouraged to talk, to laugh, even to sing. He wants to paint the truth in action - a convivial gathering of friends with food, wine, laughter and song.

One of the great pleasures of a Vreeland book is looking at the world through an artist's eyes. Renoir selects colors with the greatest of concern. For faces, he blends yellows, roses, whites and grays to show how clothing casts color on the skin and how colors change when illuminated by the sun.

One of his greatest concerns while painting the luncheon was to anchor the terrace, which jutted out from the café and above the water. He didn't want the terrace to float in space, but to be attached to the unseen café. He accomplished his goal by painting the awning above the terrace, which suggested the out-of-scene café, but while he worked, he painted his model with the canvas rolled back to allow light on their faces and their clothing.

Auguste Renoir left a brilliant legacy as an artistic genius, but he harbored some glaring flaws. While a sensitive man, wounded by the poverty he saw on the streets of Paris, he was not above using people for his own purposes. He professed to love his beautiful young model, Margot, with whom he lived for three years. He enjoyed painting her, but spent little time talking with her: "He hadn't thought to ask her why she was attracted to disreputable men, or whether her family was still living, or what was on her mind. ..." When Margot was dying from smallpox and wrote to Renoir asking that he come to her, he went to her apartment but did not go inside: He didn't so much fear contagion as he feared seeing the effects of smallpox on her beautiful face. In Luncheon of the Boating Party, Susan Vreeland has once again produced a masterwork, a resurrection of people, events and places long since gone. Like the painters Vreeland writes about, she too is leaving her legacy - some of the world's finest examples of historical fiction.

-- Linda Busby Parker

Return to Review List

CORVALLIS GAZETTE TIMES

Art, love and the river

Many people say they love art, but Susan Vreeland emphatically walks that walk, having spun her passion into a cluster of best-selling novels, including The Girl in Hyacinth Blue, dedicated to vivifying artists and their work.

However, to say merely that Vreeland brings to life Pierre-Auguste Renoir's painting Luncheon of the Boating Party in her new novel of the same title is to oversimplify her accomplishment, in much the same way that the title Renoir chose oversimplifies what his picture is about.

Vreeland's newly published book comes embellished with a reproduction of the famed Impressionist's 1880 painting of 14 convivial French men and women, which readers will turn to repeatedly as they absorb the author's recreation of its creation, her application of layers of meaning with a hand surely as deft as the one with which Renoir applied his carefully blended dabs of paint.

The reader watches as Renoir, nearing 40 and well-established in his career, conceives the idea for a work that will meld Impressionism with the traditional in "a painting designed to astonish" and capture the spirit of the day. Renoir decides he will paint from one of his own favorite vistas, the restaurant terrace of the Maison Fournaise over the river Seine. In this sun-lit spot, customers from diverse social classes enjoy their newly won leisure: Sundays off, thanks to a work week shortened by the Industrial Revolution.

As the artist gathers and poses his subjects for a series of luncheons and sittings, Vreeland alternates his viewpoint with that of half of the models, introducing the reader to their minds and diverse social lives while ever deepening and enriching the plot. The access Vreeland grants to these other narratives contributes unexpected elements of suspense and conflict.

When she first came face to face, circa 2002, with Luncheon of the Boating Party in the painting's permanent home, The Phillips Collection of Washington, D.C., Vreeland explains that she instantly knew, "as soon as I saw it," that she wanted to write its story, but that only a "multi-voiced novel" could capably "provide the different textures and various dimensions" of Renoir's world.

Intensive research here and abroad uncovered the vibrant lives of Renoir's models, from actresses to poets, fellow painters and the proprietors of the Maison Fournaise, an earthy mix of personalities apt to depict "the exuberance, the explosion of creative energy" in 1880 Paris. In her quest to highlight four levels of that milieu -"Renoir, the models' lives, la vie moderne, and the politics of the art world" - Vreeland reveals the fascinating, vivid worlds of cafés, cabarets, shops and rich salons.

The details she selects are beyond exquisitely painterly. When Vreeland depicts the act of eating a cherry with gusto sufficient to evoke the taste of it on the reader's lips, the word that springs to mind is sensuality. You don't just read this book: you can sniff, devour, fondle and listen to it, right along with the characters.

-- Pat Amacher

Return to Review List

PARIS THROUGH EXPATRIOT EYES (website)

Édouard Manet was no great admirer of Pierre-Auguste Renoir's paintings. Once he went so far as to tell Claude Monet to take Renoir aside and convince him to give it all up: "You can see for yourself that it's not his job." Monet either failed to pass along this advice or else Renoir chose to ignore it - and a lucky thing, too, because he went on to produce one of the most appealing of all of the Impressionist canvases, Luncheon of the Boating Party. Few paintings are quite so inviting. A group of people fourteen people, nine men and five women, are gathered on the terrace of a riverside caf? on a summer's day. The wine flows, the sun shines, boats drift lazily past. Who wouldn't want to join their company?

Thanks to Susan Vreeland's new novel, Luncheon of the Boating Party, we can do exactly that. Vreeland's recent collection of short stories, the charming Life Studies, introduced readers to many people who had walk-on roles in French art: Monet's gardener, Manet's wife, Modigliani's daughter. In Luncheon of the Boating Party she sets us a place at the table in the Maison Fournaise where, for eight remarkable weeks in the summer of 1880, Renoir assembles an engaging cast of characters and struggles to complete his masterpiece.

The story begins with the accident-prone Renoir crashing his steam-cycle (a nice emblem of la vie moderne) beside the Seine as he makes his way to the restaurant. He conceives the idea of restoring his flagging fortunes by painting a large, many-peopled canvas along the lines of his Bal au Moulin de la Galette, done four years earlier. The painting will be hugely important for his career, and for Impressionism more generally. A half-dozen years after the First Impressionist Exhibition, disagreements over how and when to exhibit are beginning to split the painters. Meanwhile the writer Emile Zola, once a staunch supporter, wounds Renoir with a review claiming that Impressionism has failed to produce a "man of genius." As for Renoir himself, he is approaching his fortieth birthday, grieving for a dead lover, and having no end of trouble selling his paintings. Can his giant new canvas turn things around?

Renoir's painting may show us a carefree scene, but its creation turns out to have been anything but. Renoir begins recruiting his models to pose at the riverside restaurant, eventually putting together a motley group of friends and acquaintances from Paris's salons and caf?s (through which Vreeland expertly guides us). The tricky logistics of such a large cast soon become apparent: besides modelling fees, Renoir must somehow provide food and wine for the party for eight consecutive Sundays - the time it will take to paint the work. There are other costs as well. Renoir suffers fits of despondency as he works on the canvas, which he repeatedly scrapes down and alters. He also has problems with his models: one flounces out, while another almost gets himself killed in a duel. Before long, Renoir begins running short of money for food, lodgings and pigment.

The beauty of Vreeland's novel is how she shows Renoir coming to terms with his models not merely as models but as people. To paint them, he must learn to see them as more than simply dots and dashes of pigment. He has the "vision to see hundreds of colors," but is blind, initially at least, to the lives and dreams of the people he paints. "Isn't there anything more to you than a brush?" asks one of them, Alphonsine Fournaise, daughter of the restaurant's proprietor.

It's the lives and dreams of these models that Vreeland explores, deftly filling in Renoir's blindspots and spinning a narrative by turns comic and poignant. Alphonsine is both in the center of the painting and at the heart of the novel. We learn her affecting story - an act of humanity in the midst of war - and watch her fall in love with Renoir as he paints. Her posing for him on the terrace is, she realizes, the "great moment in her life." But there's little place for Alphonsine in the painter's affections. Renoir is captivated instead by another of his models, Aline, a 19-year-old seamstress who - in another appealing vignette - sews herself a costume so she can pose in the picture.

After the canvas is finished, an art dealer tells Renoir: "Marvelous the stories you hint at in the interactions." After reading the novel we can agree: what stories indeed, delicately brushed to life in the pages of Vreeland's novel.

-- Ross King

Return to Review List

ROCK AND SLING

ROCK AND SLING: A JOURNAL OF LITERATURE, ART, AND FAITH

We Were Here, And We Loved

"Religion's everywhere.... In the mind, the heart, and in the love you put into what you do"

-- Auguste Renoir, "the painter of happiness," in Luncheon of the Boating Party

Looking to try armchair slumming in French cabarets? Maybe find your inner

bohemian? The Talmud teaches that one day we'll all be called to

answer for the permissible earthly pleasures we refused to enjoy. So

... I immersed my senses in Luncheon of the Boating Party, Susan

Vreeland's intelligent, sexy, and subtly spiritual rendering of

late 19th century France.

"Place Pigalle on a summer night sizzled like rancid butter in a hot pan....

the yellow gaslight, the blare of a trumpet spilling out of a cabaret

... Models lounged on benches to attract painters ... They spotted

Renoir and backed him against the wall."

Ah, Impressionism-the attempt to capture on canvas a fleeting instant

in time. Not unlike a poem. In her fourth historical novel, Vreeland,

admired the world over for deliciously reanimating the lives and

creations of famous artists (as well as the lives that they and their

works touch), shows us the early modern age. La vie moderne

emerges from despair, humiliation, and the economic chaos triggered

by the Franco-Prussian War and the 1870 Siege of Paris. A year later,

Parisian insurgents retake their city; optimism flares; and a shamed

people feel their way out of darkness toward light and life. Post-war

relief makes morality elastic, and hedonism ensues. But creative

energy also burgeons; the arts flower.

Auguste Renoir's passion for joy and beauty and, well ... sex, is

reminiscent of another prolific genius (think Mozart in Amadeus),

yet in both lives I see an acknowledgment of God the creator. "Some

say a tree is only made of chemicals," Renoir tells Alphonsine, a

potential girlfriend, "but I believe that God created it." If he

sullies his "Christianizing" effect by adding, "And that it's

inhabited by a nymph," it's partly to make her giggle. He's a

charmer. Sometimes he's a chauvinist. Vreeland is true to what's

known about the painter. She writes with the care of a biographer as

well as the heart and wit of a poet. In recreating an actual era as

well, the novel's overall pace takes its time, like a seduction.

It's not just Renoir's playfulness on display; she depicts a

middle class slowly rediscovering pleasure. Hope. Recreation.

Times are also ripe for a new kind of painting-"To let the world know

after our time that we were here," says Alphonsine, "and that we

loved." Renoir agrees. Too poor to afford the supplies for the

large painting he envisions, he nevertheless imagines 14 models

posing for him each Sunday. "It's what I can do now, when the

light is right and I have no commissions in Paris." Weekly, he will

empty his wallet at Maison Fournaise on the Seine to feed the 14 as

well as provide "the set," a table on the terrace laden with food

and wine. He hopes to rock the stodgy academy with what will become

his masterpiece.

But who will pose? For his subversively informal composition (a

mind-bender for old-school snobs of the Salon), Renoir invites a war

hero, an Italian journalist, a Folies Bergère mime, and

others. He fails to foresee an imminent love triangle when his models

also include the restaurant hostess (a war widow with a shameful

secret) and his former lover. One of the women will even "do a

boulevard" (streetwalking gig) to raise extra cash to ensure the

painting's completion. Unsavory as this will be for some readers,

Vreeland's handling of the woman's sacrificial love comes across

as true to the times and culture. "Here was the spirit of

Montmartre, alive and beating, sensuality as a fully generous act."

(Spoiler alert for those getting nervous: there's gentle redemption

in the works.)

If you ask me, Renoir should have seen "the woman thing" coming

("Her creamy skin glowed from within, like a lit candle in a dim

church ..."). Early on he confides to a friend, "I only want to

paint women I love, or imagine I could love." And later: "[I]t

wasn't philandery ... It was compulsion. To adore what he painted.

To do brilliant work not out of technique but out of desire ..."

Which also sums up what Vreeland has accomplished in writing this

book. For the most part, meticulous research merges seamlessly with

story. The identities of the models are true, although the last face

Renoir paints remains a mystery. (A fine reproduction of the painting

midway through the book allows checking one's impressions of

characters against their portrait.)

Like the best paintings (and poems), many layers comprise the work. Think

of them as scrims of color, or undercurrents: Jealousies and fears

play out beneath poses. On a practical level, as if peering over the

artist's shoulder we learn about the exacting placement of

pigments. We also view French society in transition: morphing class

borders, the rise of feminism and leisure pursuits. I found myself

occasionally wishing for more details on the war and political

climate-information easily enough looked up afterward. And this is

a book you will think about after closing the cover.

But what about all the sensuality, you ask? One can almost smell the

pigments and turpentine, feel the dance of the brush, the stirring of

passion: "The blossomy, weedy smell of the oil, the solidity of

the paint on the palette giving way to plasticity with his brand-new

brush as tight and springy as a virgin, as lively as a whore. His

pulse raced as though he were a raw novice." There's raw honesty

here, naming desire, yet creatively, tastefully. So much of

contemporary Christian fiction dodges the sexuality of its

characters. Renoir is a man of his times, a man ardently in love with

life. And this is, above all, a love story.

On another level, the novel is a tribute to art standing on the

shoulders of those who come before. It's also an extended metaphor

for creative process. "You see the whole, don't you?" a friend

says of Impressionist painting. "We see only marks." For me,

Renoir's response is a human echo of God's redemptive vision for

humanity. He says that what he will see in the work later is already

present, waiting to be discovered.

Over the course of the story revelation steadily emerges for the reader.

Some of the figures in the painting are turned away from the viewer

(yes, egos clamor at first). Ultimately, each makes their presence

felt; each contributes to the overall design. Alphonsine profoundly

moved me. "She had to know if Auguste could give her what she

needed," not just forgiveness for all she had betrayed, "but

understanding." Her forgiveness, in turn (mustn't spill the beans

here), and her growing capacity for Christ-like love surfaces

quietly: a faith cameo within the larger portrait, glimpsed like the

back of a head.

Ongoing tension in the book arises from Renoir's combined artistic and midlife crises.

Admitting to Alphonsine that he's nearing forty and still merely "setting

down what he sees," she asks, "Is that an issue of faith?"

"If I were to paint what I see right now," he answers, "it wouldn't

be my invention. It's just what has been given me-by God, if you

will, or by the current of life. Why not think it was made so

gorgeous for me?"

Luncheon of the Boating Party unfolds via compassion and a keenly

observant eye. If the abundance of French expressions and locales

slow the reader initially, it's soon obvious that clarity will

consistently arise from context. Like layers of paint, the milieu is

built up gradually, creating texture and depth. Although it's a

book about a masterpiece as end product, it's also about process.

As Renoir says, "I'll keep making discoveries until the very end.

Sometimes the most important things come out last." The conclusion

of this gently paced novel shook me, mind and emotions. I sat a long

while, just staring.

A story this good leaves me eager to haunt a museum, or sign up for the

next art history class, or at least invite fascinating friends to lunch.

Lastly, "It's important to see in a thing the person who made it."

Renoir says this when choosing hand-blown glasses for the table

setting. In Vreeland's vibrant ode to art, forgiveness, and

humanity, she reveals an equally lively and lovely soul.

-- Laurie Klein, Consulting Editor, Rock & Sling

Return to Review List

|