|

The Genesis of the Book

|

|

If it weren't for the zest of the Victorians to write frequent, voluminous letters, this book would never have come to be. More significantly, Clara Driscoll would be only a footnote in the history of decorative arts in America. However, thanks to her spirited letter writing to her family in Tallmadge, Ohio about her life in Manhattan working for Tiffany Studios, we know her as artist and woman--highly talented, keenly inquisitive and adventurous in what was then a man's city, and uniquely important to five very different men.

|

|

|

Clara Driscoll in her workroom at Tiffany Studios with Joseph Briggs,

1901. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

|

|

|

By a remarkable coincidence, three individuals unknown to each other, a distant relative of Clara Driscoll, a Tiffany scholar, and an archivist at the Queens Historical Society, each aware of only one collection of Clara's letters, brought the correspondence to the attention of two art historians steeped in the work of Louis Comfort Tiffany, Martin Eidelberg and Nina Gray. Astonishingly, they were informed of two treasure troves of letters within just a few days of each other in 2005--one collection owned by Kelso House Museum in Kent, Ohio and housed at Kent State University Library, the other owned by the Queens Historical Society.

This result was electric. The art historians learned of each other, came together in a scholarly partnership, and were shortly joined by Margaret K. Hofer, Curator of Decorative Arts at the New York Historical Society which owns a substantial collection of Tiffany lamps, including 132 from one donor, Dr. Egon Neustadt. It was immediately clear to the team of three that NYHS was the perfect venue to mount an exhibition and share what was contained in the letters with the public. A revelatory and fascinating 200-page catalog of the exhibition, A New Light on Tiffany: Clara Driscoll and the Tiffany Girls, was written by the three curators for the opening of the exhibition in 2007, and has been my major published source.

In it, Clara is recognized as "a gifted unsung artist, an eyewitness to the making of some of the twentieth century's most beautiful and beloved designs." Her letters have "transformed [the] understanding of the design and manufacture of Tiffany objects, including lamps, windows, and mosaics." Equally important, the letters have revealed "the crucial role played by women" at Tiffany Studios.

|

|

|

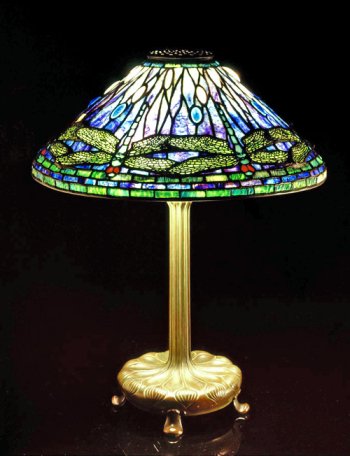

Dragonfly and Water Lamp, designed by Clara Driscoll. From the collection of The Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art, Winter Park, Florida, © Charles Hosmer Morse Foundation, Inc.

|

|

|

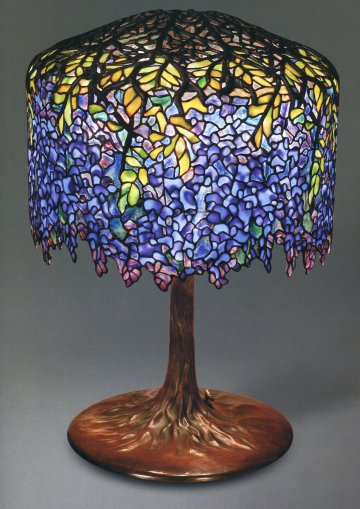

All of the pieces were in place to rock the art world, including Tiffany collectors who had been led by company brochures to believe that the iconic leaded-glass Tiffany lamps were products solely of Louis Comfort Tiffany. In 1907, close to the end of Clara's tenure at Tiffany Studios, a company advertisement stated, "A lamp may be as much an object of art as a painting or a piece of statuary. In fact, it should be." No mention of Clara or the women's department there. Never once was she acknowledged publicly by Mr. Tiffany during more than three decades of promotion and advertising. Yet "Clara Driscoll was, in effect, the hidden genius behind many of Louis C. Tiffany's designs," states the NYHS exhibition catalog. "Although not specifically stated in her letters, it was possibly Clara who hit upon the idea of making leaded shades with nature-based themes...It was not until about 1898 that the first leaded shades appeared--in other words, coincident with Clara's return to Tiffany studios. In June 1898 she reported that three of her leaded shade designs had already been put into production."

|

|

|

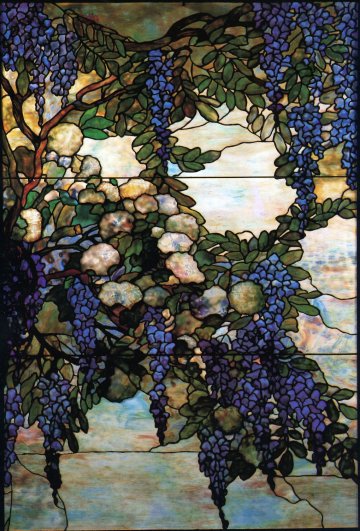

Wisteria Lamp, designed by Clara Driscoll. The Lamps of Louis Comfort Tiffany, by Martin Eidelberg, et al. Vendome Press, New York, 2005.

|

|

|

Enter yours truly.

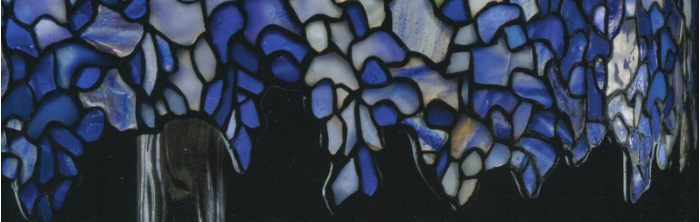

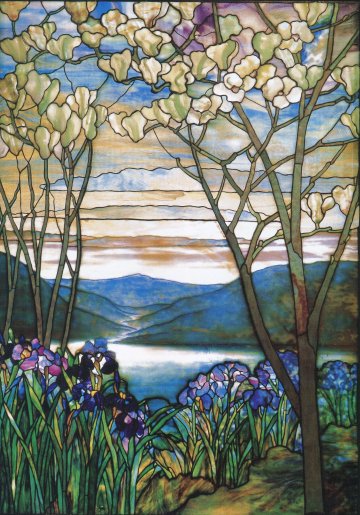

I was in New York for the launch of Luncheon of the Boating Party in May 2007, and I had a couple of hours free so my art-loving agent and I made a dash for the Metropolitan Museum of Art to see an exhibition recreating the lavish fountain court of Tiffany's Long Island estate, Laurelton Hall. Never had I seen leaded-glass windows up close. The subtle swirls of pastel hues, the jewel-like depths of darker colors, the folds in glass as if still molten, a fringe of wisteria in a series of windows, a screen of three-dimensional magnolia blossoms, glass flowers on the capitals of columns, the atmosphere of a pleasure palace all entranced me. In awe, I could only think that an artistic genius created this splendor.

|

|

|

Snowball and Wisteria Window.

|

|

|

Coincidentally, a New York Times review of the NYHS exhibition was brought to my attention. We squeezed that in the next day, and I returned for a better look the day after. I was astonished at the beauty and creativity of Clara's lamps, and was fascinated that there was a group of young women who had made them.

In the exhibit, I read a few of her displayed letters. Here was the lively, sometimes rhapsodic voice of a woman who bicycled all around Manhattan and beyond, wore a riding skirt daringly shorter than street length, adored opera, followed the politics of the city, and threw herself into the crush of Manhattan life--the poverty of crowded immigrants in the Lower East Side as well as the Gilded Age uptown.

|

|

|

Tiffany Girls on the Roof of Tiffany Studios, 1904-05. From the collection of The Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art, Winter Park, Florida, © Charles Hosmer Morse Foundation, Inc.

|

|

|

But what about the other Tiffany Girls photographed on the roof of Tiffany Studios and at Coney Island? What were their lives like? They worked anonymously even though Tiffany considered them talented artists with keen color sensitivity. To discover their backgrounds, even their names, and where they stood in the wealthy-to-impoverished population of the city, I had to turn to the exhibition catalog which I devoured during my tour--speaking publicly about one book and thinking privately about the next.

|

|

|

Magnolias and Irises Window, designed by Louis Comfort Tiffany. Department of Decorative Arts, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

|

|

|

Reading at home, I found much about Tiffany and learned that he was the creator of a vast array of new, expressive kinds of glass, an innovator of style and execution of windows, a bold originator of the ecclesiastical landscape window, and a passionate pursuer in the quest of beauty, but I found only an infrequent vague reference to Clara. There was no way around it. In order to determine whether or not I would actually write this novel that hung there enticing me, I traveled to Kent, Ohio to bury myself in her correspondence, as I did later in Queens, New York.

Clara's letters revealed that she was independent and self-sufficient, talented and ambitious, educated and self-educated, emancipated to a degree, opinionated, wry, vibrant, and hungry to grasp all that life in the nation's cultural capital had to offer--an embodiment of the New Woman. In short, she entirely captivated me. Precisely because she was largely undiscovered but sure to make an impact, she was a historical fiction writer's gold, complete with yearnings, inner and outer conflicts, triumphs and defeats, romance, and close relationships with five men. What's more, her letters revealed a colorful cast of characters swirling in and out of her life at the studios and in the boardinghouse she shared with other artists and quirky individuals rollicking on the edge of bohemian life. It was a New York setting charged with change, excitement, and recognizable and beloved spots.

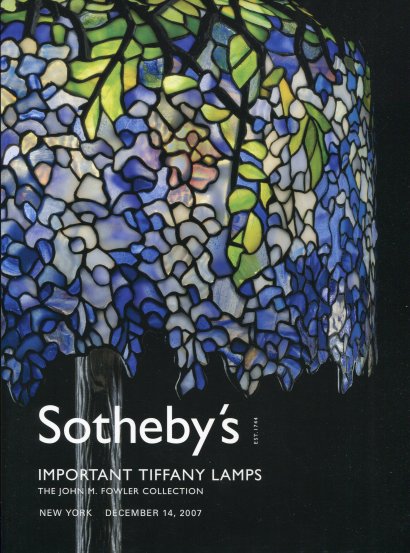

While in New York a second time I interviewed Nina Gray and Margaret K. Hofer, two of the three curators of the NYHS exhibition; Lindsy Parrott, Collections Manager and Curator, and Susan Greenbaum, Conservator, of the Neustadt Tiffany Collection at the Queens Museum of Art; Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, Curator of American Decorative Arts, Metropolitan Museum of Art; and Arlie Sulka, Owner and Managing Director of the Lillian Nassau Gallery, the first to exhibit the lamps after Tiffany Studios went out of business. These experts spoke of Tiffany in ways that brought him to life for me. As an exquisite treat, I went to an exhibition of the lamps of Tiffany Studios at Sotheby's auction house. Clara's most iconic designs were there--Dragonfly and Wisteria--with suggested bids of $450,000 to $600,000.

|

|

|

|

Important Tiffany Lamps: The John M. Fowler Collection. Sotheby's, Inc. 2007.

|

|

|

Then, I settled down at home to six months of intriguing research, piecing together like a Tiffany Girl myself the narrative upon which my imagination thrived

|

|

|